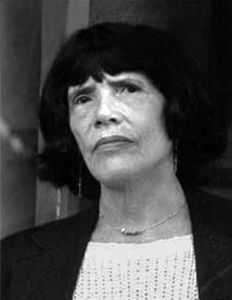

Leni Alexander was a committed artist throughout her life: her work was marked by experiences of repression, political action, and an irrepressible interest in her fellow human beings. Life and art were inseparable for her. The musical genre for which she became famous therefore seems almost symptomatic: Radio theatre. Her autobiographical radio plays allow Leni Alexander’s life to be told also through her works.

Life Is Shorter Than A Winter’s Day or Par quoi? À quoi? Pour quoi? (WDR 1989)

“Discha, Discha…”: the radio play begins with these calls. It is based on the experiences of Leni Alexander, who was called Discha by her stepfather – a Jewish girl suffering the horrors of fascism. Between the descriptions of her school days, Alexander mixes arrangements of her own music, Yiddish songs, but also Chilean protest songs. The latter was because the events in Chile thirty-five years later awakened memories in her of her flight from Germany.

Alexander was nine years old when the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933. Together with her mother, the singer Ilse Pollack, and her stepfather Siegfried Urias, she experienced the repression against Jewish citizens in Hamburg. However, it was not until the pogrom night in 1939 that the family was forced to flee. In her exile in Chile, Leni Alexander soon received music lessons again, and later studied psychology at Montessori education. In 1949 she also began studying composition with the Dutch composer Fré Focke. Through him, Alexander got to know new musical worlds:

“I felt that doors were opening whose existence had been unknown to me until then. Behind these doors I was able to discover a music, a way of thinking about and listening to music that was a revelation to me from that moment on.”

In 1954, Alexander received a scholarship from the French state, and was able to establish close contacts in Europe with composers such as René Leibowitz, Olivier Messiaen, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono. As formative as her work with the European avant-gardes was, she was at odds with their sometimes elitist understanding of art, in which – according to Alexander – technique took precedence over musical creativity. Perhaps it was due to her rejection of politically rigid systems that she also avoided any dogmatism in music, but also as well as clear hierarchies. Most of her compositions are atonal, and assign a high degree of co-responsibility and freedom of choice to the performers.

On her first visit to Cologne in 1960, Alexander’s only choral work, her cantata From Death to Morning, was premiered. She had composed the work for the World Music Festival of the International Society for New Music.

At the end of the 1960s, Alexander initially went back to Chile. A period of constant moves between Chile, Europe, and the USA followed until 1969, when Leni Alexander moved back to Paris with her youngest son due to a Guggenheim scholarship. Her second stay became a renewed exile in 1973 because of the military coup in Chile. She then deepened her political commitment, working for Amnesty International and various Chilean solidarity organisations.

Chacabuco, the Story of a Ghost Town in Chile (WDR 1993)

Here Alexander denounces Pinochet’s crimes, as well as the involvement of European governments in Chilean politics. The ghost town of Chacapuco served as a prison camp after the military coup, where miners were exploited in the saltpetre mines there – mines from which European companies particularly profited. Alexander mixes popular music from northern Chile, verses by Pablo Neruda, and Goethe’s Faust, with recordings of the composer’s conversations with a miner and a former prisoner of the prison camp.

Leni Alexander financed her living in Paris through numerous scholarships, composition commissions – for example from Radio France – and music lessons for children. She also continued to be active in South America: on an Argentinean concert tour, she met the Frankfurt Ensemble Modern. This encounter led to a collaboration at the Cologne Festival Experimentierfeld: Frauen-Musik zur Aufführung (Field of Experimentation: Women’s Music for Performance) in 1984. At the end of the 1980s, the composer went back to Chile. However, until shortly before her death, she spent several months each year in Paris and Cologne, composing and developing radio pieces mainly for the WDR. Leni Alexander died in Chile on 7 August 7 2005 at the age of 83. In 2013, her heirs donated a large part of her estate to the Archiv Frau und Musik in Frankfurt.

The Story of the Chariot. Reflections and Thoughts During a Journey in the MERKABAH Wagon Concerning Primordial Beings (text manuscript 2001).

In her unfinished audio piece, Alexander once again calls for “not forgetting”. The chariot Merkahba – in Jewish mysticism the throne chariot of Ezekiel – flies through the landscape towards “the history of creation”. At the end of the text is the admonition: “The memory of all that is past must not be lost, just as human history belongs to us forever, it gives us life, in which there is no room for forgetting.”

More information on Leni Alexander can be found at:

- Musik und Gender im Internet

- Lexikon verfolgter Musikerinnen und Musiker während der NS-Zeit

- MusikTexte, Heft 107, 11/2005, p. 33–46.

A personal essay on Leni Alexander has been published in the Digital German Women’s Archive as part of the project #WoraufWartenWir? (What Are We Waiting For?).

Wenn Sie dieses Video ansehen, erklären Sie sich einverstanden mit den Datenschutzrichtlinen von Youtube.

Wenn Sie dieses Video ansehen, erklären Sie sich einverstanden mit den Datenschutzrichtlinen von Youtube.

Wenn Sie dieses Video ansehen, erklären Sie sich einverstanden mit den Datenschutzrichtlinen von Youtube.