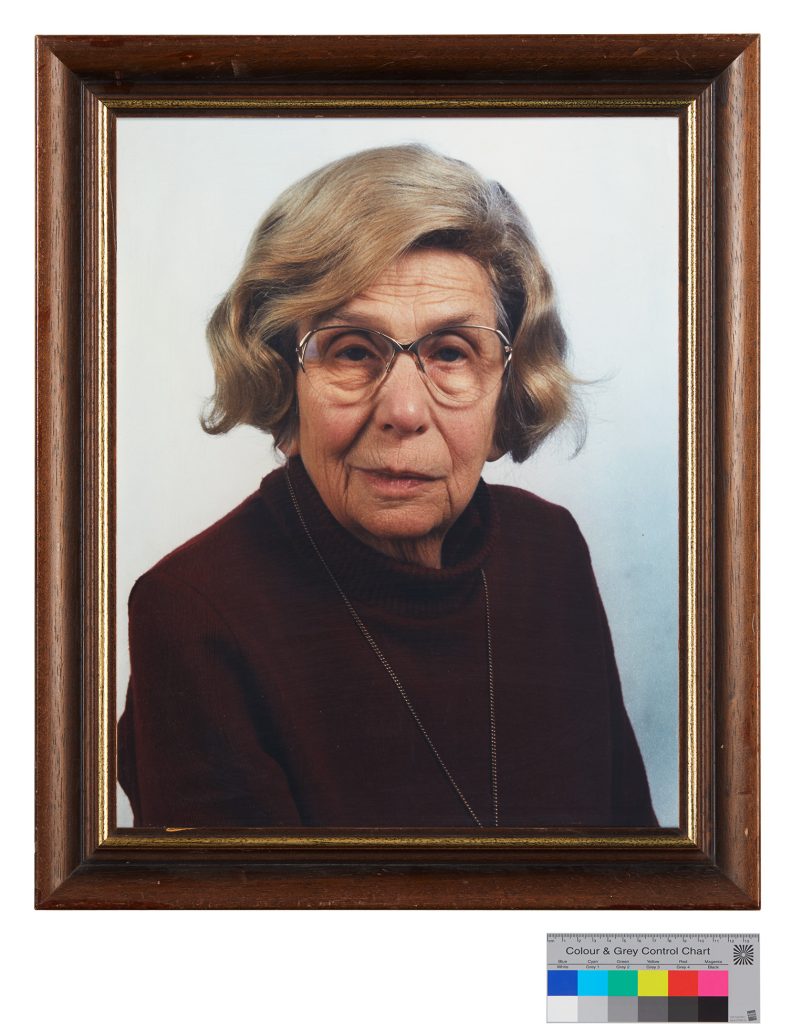

Felicitas Kukuck was born on 2 November 1914 as the daughter of Prof. Dr. med. Otto Cohnheim, and his wife, the singer Eva Cohnheim. In 1916, her father changed his Jewish name to Kestner. Felicitas was thus also given the surname Kestner.

Even before her first piano lessons, Felicitas Kukuck developed a strong love of music. In her diary, she describes singing little verses from the picture books her mother had read to her. Thanks to piano lessons starting when Felicitas Kukuck’s was ten, the improvisations she’d done with her brother were “steered into orderly channels”. Miss Wohlwill, who was already teaching Kukuck’s older sister, played her the A-flat Major Etude by Chopin at that time. In an interview with Ulrike Loos, Kukuck describes this experience as a kind of awakening moment: “In that piece, all the magic of sound was captured on black keys”. Along with her piano teacher, Felicitas Kukuck’s mother was her greatest supporter. Eva Cohnheim was an alto singer, and Kukuck began to accompany her on the piano at an early age: “[…] Then she strongly encouraged me to learn how to accompany songs. And I did that with delight. Brahms songs, but also difficult things, like Schubert and such. But then she also asked me to play arias from the St Matthew Passion, which is of course even more difficult. Of course, I didn’t know how to do that at the age of ten. But still I accompanied her again and again.”

Felicitas Kukuck’s lifelong connection to vocal music can also be traced back to these experiences, as this is how she learned to think of composition from the perspective of singing: “You always have to know where the breathing is.”

“By the way, silence was my survival tactic.”

Felicitas Kukuck only found out she was Jewish after the National Socialists came to power, and she was classified as a “quarter Jew”, and subsequently denied the opportunity to study at the Academy for Music Education and Church Music in Berlin. She already experienced the first repressions during her school years. After the Lichtwarckschule was brought into line in 1933, and the headmaster Heinrich Landahl had to leave, a “180 per cent Nazi” took his place, according to Kukuck. She then left the school. Nevertheless, emigration was never an option for Felicitas Kukuck: “I wanted to stay in Germany, in the land of Bach and Mozart and Brahms and Schubert.”

In 1936, she passed the state private music teacher’s examination in piano, but was not granted a teaching permit because she was Jewish. She therefore decided to remain at the conservatoire as a student. In her last two years at school, she had learned to play the flute, and was thus able to study this instrument without taking an entrance examination. Gustav Scheck became her teacher; a flutist and music teacher from Freiburg. In 1936, on the advice of her harmony teacher, Kukuck went to Paul Hindemith’s composition class. The composer described this event as a turning point in her life. Thus, from 1937 until Hindemith’s emigration in 1938, Felicitas Kukuck attended his classes three to four times a week. According to her own statement, Felicitas Kukuck had no problems with National Socialists at the conservatoire. Apart from the then director of the conservatoire, on whose discretion Kukuck could rely, no one knew of her Jewish ancestry. Therefore Felicitas Kukuck had no further restrictions during her studies, apart from the fact that she could not take her desired course of studies to become a music teacher. When, at the beginning of 1939, a law was passed at stating that all “Jews and Jewish half-breeds who had changed their Jewish name” had to adopt it again, her friend Dietrich Kukuck unceremoniously ordered a wedding banns. He found a registrar to whom he did not have to present Felicitas’ birth certificate with the name Cohnheim and the ancestral passport. On 3 July 1939, the two were married in a civil ceremony.

“Language is something that can be composed.”

As a composer, Felicitas Kukuck saw herself very much in the tradition of Paul Hindemith: “My music, my compositions, are tonal. I refer to the overtone series, where the different intervals also have different place values. Octave and fifth are the elementary intervals because they have the simplest vibration ratios.” Kukuck emphasises this in a 1988 conversation with Ruth Exter, in which she describes her composition process using the example of a vocal work: “[…] The next step is then to compose a melody that relates to this text or sections of text. I then also check this melody with regard to the realisation of my compositional principles […]. After this compositional step, I check the harmonic coherence of my compositions by composing the second voice of a bass line to the melody. This voice serves to establish the harmonic shape of the melody and can therefore certainly be changed again later.”

Felicitas Kukuck always used texts as the basis for her compositions. Folk songs, Christian texts from chorales or psalms, as well as poems, were in many cases the starting point for her compositions. The importance of texts for Felicitas Kukuck becomes impressively clear in the interview with her daughter. She begins by saying that she did not write any compositions about her experiences during the Second World War, because art and war did not go together for her. When asked by her daughter why she then composed a requiem about Hiroshima, Felicitas Kukuck replied that she did not set music to the war, but to a very good text.

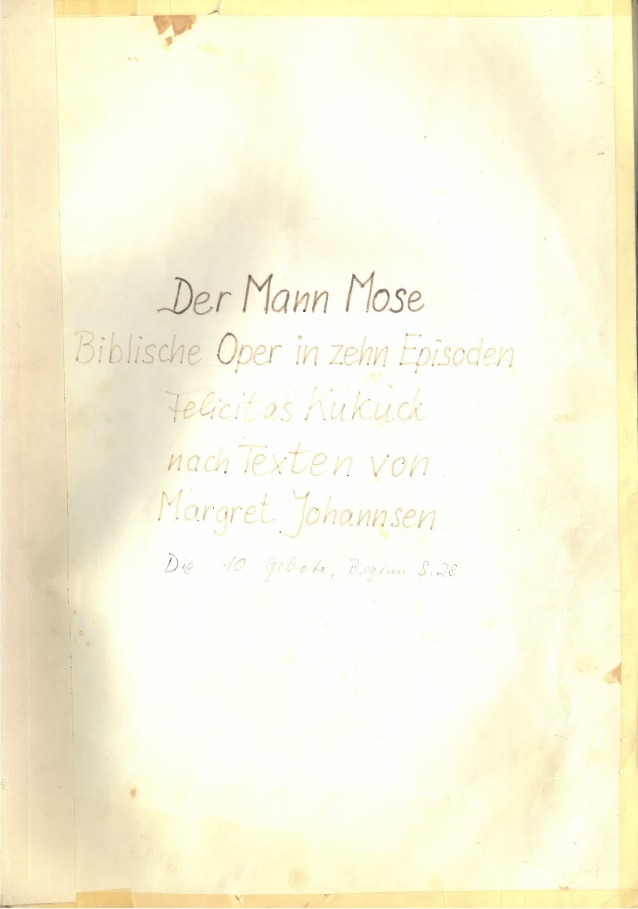

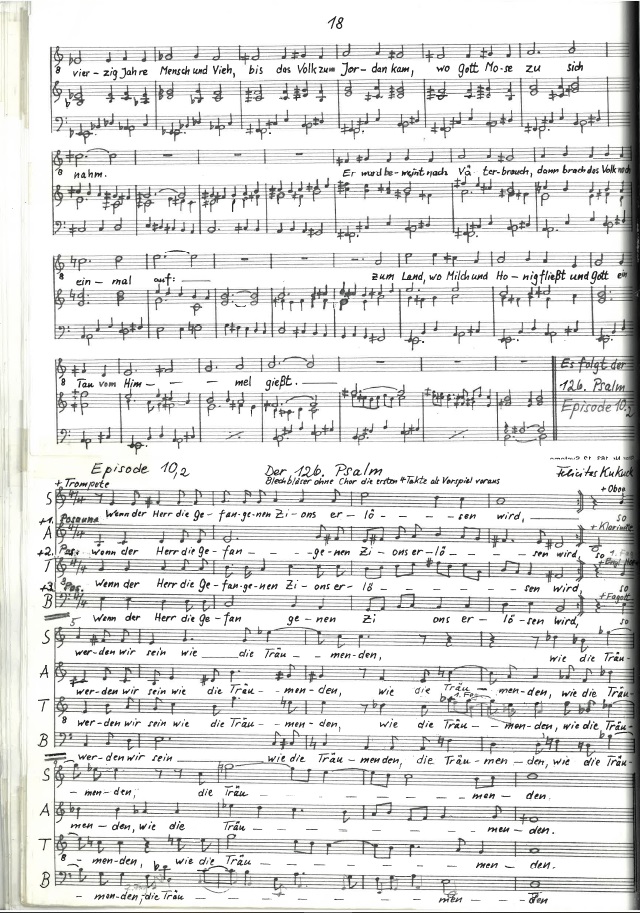

Felicitas Kukuck composed over 1000 works during her lifetime. These range from so-called “utility music” to full-length compositions, such as the opera Der Mann Mose, or her Passion Oratorio Der Gottesknecht.

Felicitas Kukuck died in Hamburg-Blankenese on 4 June 2001. In 2004, her daughter Margret Johannsen gave her extensive estate to the Archiv Frau und Musik.

Further literature and sources (German):

- Erbengemeinschaft Felicitas Kukuck: Felicitas Kukuck. Leben und Werk der Komponistin, http://www.felicitaskukuck.de.

- Johannsen, Margret, Felicitas Kukuck, in: Musik und Gender im Internet, https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/artikel/Felicitas_Kukuck

- Brandt, Siewert: Interview mit Felicitas Kukuck, [unveröff.], Original im Archiv Frau und Musik, Nachlass Felicitas Kukuck, N-R CD-B-3.

- Johannsen, Margret: Interview mit Felicitas Kukuck 1-3, 1997 [unveröff.], Original im Archiv Frau und Musik, Nachlass Felicitas Kukuck, N-R CD-B-3.

- Kukuck, Felicitas: Sonate für Sopran-Blockflöte und Klavier, auf: 1. GEDOK-Konzert 1967 [unveröff.], Quelle: Archiv Frau und Musik, Nachlass Felicitas Kukuck, N-R CD-B-4.

- Loos, Ulrike: Gespräche mit Felicitas Kukuck über die Musik, 1993.

- Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk: Allein zu dir. Neue Musik für Blockflöte und Cembalo, Radiosendung vom 21. April 1953, Quelle: Archiv Frau und Musik, Nachlass Felicitas Kukuck, CD-B-2, Drei Radiosendungen.

- Exter, Ruth: Felicitas Kukuck. Biographie und Musik einer Komponistin im 20. Jahrhundert. Hausarbeit zur ersten Staatsprüfung für das Lehramt, Hamburg 1988.

More recordings can be found on the website of the heiresses at:

Wenn Sie dieses Video ansehen, erklären Sie sich einverstanden mit den Datenschutzrichtlinen von Youtube.